Several years ago, a friend of mine, Brian Zipse, the former editor of Horseracing Nation, penned a column titled “I’ll take my eyes over your numbers every time.” In it, he discussed an argument he had about Triple Crown champion Seattle Slew and arguably his most famous son — A.P. Indy.

I’ll let Brian explain what happened next.

“An industry person recently tried to compare favorably the running ability of A.P. Indy versus his daddy, Seattle Slew, by saying that the son ‘had better numbers’ than his sire,” he wrote.

“Our brief conversation took place online, so the other person could not see my reaction. I laughed, and then I shook my head with a mixed feeling of sadness and disbelief. His comment ended our brief debate, for I believed anything further would be less desirable than sticking my forehead under a dripping faucet for the rest of the morning,” Zipse continued.

“With all due respect to A.P Indy, who was a fine racehorse, and then went on to be an outstanding sire, but he was in no way, shape, or form, the runner that his father was.”

Obviously, Brian was not — and is not — alone in his opinion. My guess is the vast majority of racing fans would agree with his conclusion here… but does that make the case that observation trumps numerical analysis?

I don’t think so.

In fact, I contend that sight is among the least reliable human senses — if only because we put so much stock in it, despite not always being able to process what we see. (Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium at the Rose Center for Earth and Space, once noted that optical illusions should be called “brain failures” and he’s right).

I don’t think it’s even debatable that, generally speaking, folks are more apt to believe something they “saw with their own eyes” than something they read about, even in a scientific journal or some other credible source.

Think about it: Most folks that believe in Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster and/or little green men asking them to “take me to your leader” do so because they (supposedly) saw them — not because they found the evidence of their existence overwhelming.

What’s more, according to the Innocence Project, a non-profit legal clinic dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted people through DNA testing, “eyewitness misidentification testimony was a factor in 72 percent of post-conviction DNA exoneration cases in the U.S., making it the leading cause of these wrongful convictions.”

Simply put, numbers and statistics — when properly analyzed and applied — are far more reliable than one’s peepers. The problem is, they aren’t always properly analyzed and applied.

Too often, people use data solely to support whatever conclusion they’ve already drawn, with no thought — or even concern — as to what the numbers might actually show.

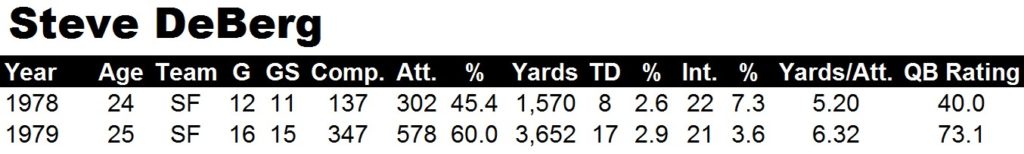

Take, for example, the case of former NFL quarterback Steve DeBerg.

By ignoring context, one would have to conclude, based on stats, that DeBerg miraculously transformed himself from a poor passer to a highly proficient one in a single year (I can already see Josh Allen fans reading with renewed interest).

DeBerg went from completing just 45 percent of his passes in 1978, to being just one of four players (oh, how the times have changed) to complete at least 60 percent of his pass attempts in 1979 (Dan Fouts, Ken Stabler and Archie Manning were the others).

But there was more to the story — much more. In addition to ‘79 being DeBerg’s second year in the NFL (no small consideration), it was also the year that a guy named Bill Walsh took over as head coach of the San Francisco 49’ers.

Prior to Walsh’s arrival, San Francisco had won more than seven games in a season exactly four times since 1958. The team had never won a championship of any kind since joining the League in 1946.

Walsh and his innovative “West Coast” offense, which stressed shorter, timed passing routes literally revolutionized the pro game — and I think it’s fair to say that it salvaged the career of DeBerg, who wound up playing until he was 44 years old (he came back for one more season in 1998 after retiring five years earlier).

The point here is numbers don’t exist in a vacuum. They must be evaluated in light of other relevant factors. However, the huge advantage that numbers provide over mere observation is that they give us something measurable, something concrete. Let’s be honest, Secretariat’s Belmont was not great because he won by an eye-catching 31 lengths — lots of mediocre horses have won by daylight margins, especially in steeplechase and hurdle events.

What made Secretariat’s Belmont great was that he completed a mile and a half in 2:24 — a mark that no three-year-old has come close to since.

For the record, both Seattle Slew and A.P. Indy won the Belmont Stakes. Slew was clocked in 2:29-3/5 over a “muddy” track, while A.P. Indy was timed in 2:26 over a “good” track.

Let the debate continue…